Merry Propheteers Promote Impossible Economic Growth

Put two economists in a room and you might think you’re in for a snooze-fest. Today’s Wall of Shame honors are shared by three, but what they have to say won’t put you to sleep. It ought to scare you to death.

It all starts with this column in National Review by Veronique De Rugy:

John Cochrane Is Right about the Incredible Power of Economic Growth

Here Rugy celebrates what I’ll call the transgressions of economist John Cochrane in an interview last September on Uncommon Knowledge. This used to be a public television show, but is now simply a video series produced by the very conservative Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

In the video, interviewer Peter Robinson sets the stage by quoting his guest from a Wall Street Journal piece:

“From 1950 to 2000, the US economy grew at an average rate of 3.5% annually. Since 2000, it has grown at half that rate: 1.76%. America’s foremost economic problem is sclerotic growth.”

I am excited to add “sclerotic” to my ever-growing glossary of disparaging adjectives used to describe slow economic growth (lethargic, sluggish, anemic, etc.) Points to Cochrane for coming up with a new one. I’m sure, like me, he was tiring of the others. Note to Cochrane: try “healthy.” When we are in overshoot, robust economic growth is not healthy. Rugy shares why she likes this interview so much, misusing “healthy” in the process:

“Robinson notes that with healthy economic growth you can double standards of living in one generation.”

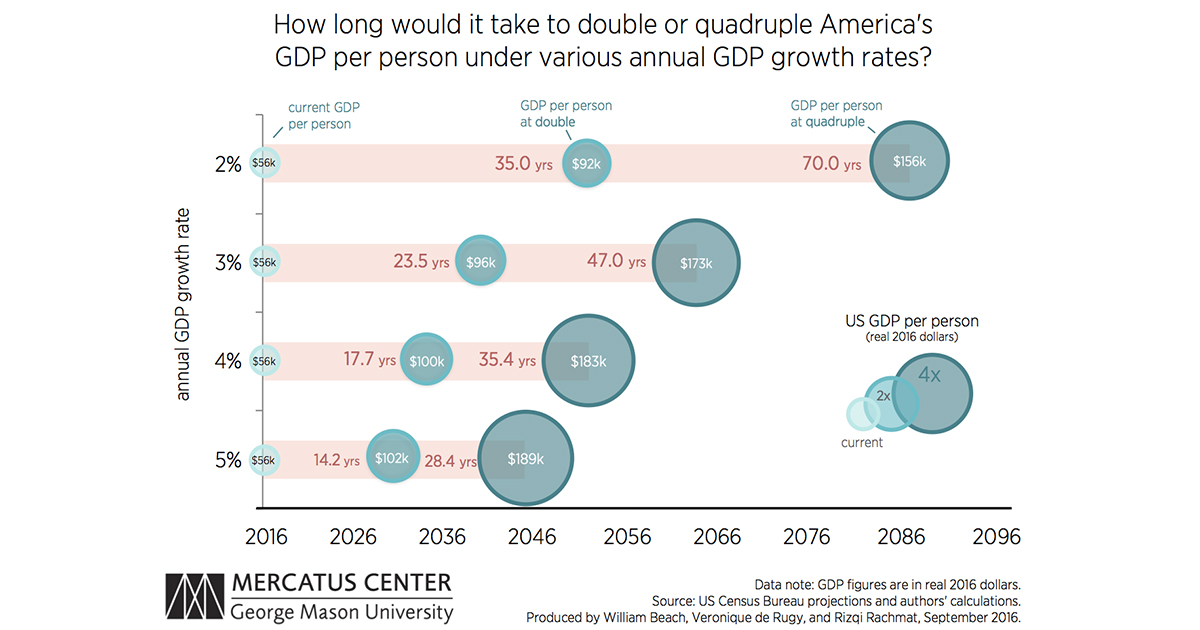

Seriously, equating GDP with “standard of living” is overly simplistic, if not completely off-base. Before we went into overshoot and began liquidating the planet, she might have been half right. Today it’s not hard to make the case that further GDP growth in the (over)developed world creates more problems than it solves. She goes so far as to share a chart she created (above), “that looks at the impact on GDP per capita under different growth scenarios and found that the payoff of higher and sustained economic growth in our lives is hard to overstate.”

I find this is a useful chart for showing just how dangerous (and fortunately impossible) perpetual economic growth can be. What I find ludicrous is that Rugy makes a very strong case for the destructive power of exponential growth, but doesn’t realize she is arguing against herself. She thinks this is wonderful:

“At the end of 2015, the US gross domestic product (GDP) stood at $18.3 trillion. If the economy were to grow from that point on at a long-term, inflation-adjusted rate of just 2 percent per year, then it would take 35 years before the size of the economy doubles. If the economy were to grow at a sustained average rate of 3 percent per year, it would take 23.5 years to double — that’s 11.5 fewer years than the scenario above — and 47 years to quadruple America’s GDP. And, if the economy were to grow at a sustained average rate of 4 percent, it would take only 17.7 years to double and 35.4 years to quadruple. At rollicking 5 percent growth rate, the US economy would double in 14.2 years and quadruple in 28.4 years.”

She needed to do a little more math. If the U.S. economy were to double every 14 years for the next century, that $18 trillion 2015 economy would hit $2,342 trillion. How does Rugy think we’ll power that? Where does she think we’ll put the CO2 and other waste products from that much economic activity? I’m sure she believes we’ll find substitutes for every scarce non-renewable resource, and – besides – we’ll completely decouple economic growth from resource extraction and waste production. That’s a serious case of optimism on which I’m not willing to bet my children’s future. If you, Rugy, Robinson or Cochrane want to catch up on realistic, science-based information about a sustainable economy, I refer you to the reading list at More About Limits to Growth.

Of course, these three are not alone in their blind faith in the wonders of economic growth. In the interview Cochrane reminds us of a myth driving so much public policy debate:

“…how are we going to pay for the national debt? If the economy doubles in size, it’ll be easy. If it doesn’t, it’ll be much, much harder.”

Yes, so easy, if only we didn’t have to deal with peak energy, peak water, peak soil, and climate change. Rugy goes on to write:

“Changes in policies, however, can make all the difference in the world. Deregulation and corporate-tax reform (done properly) as promised by President Trump, in particular, could make a dramatic difference to our rate of economic growth. We can’t overstate the importance of reining in regulations.”

The Cochrane interview offers some very interesting ideas about tax reform. There may be some wisdom in there. But Rugy’s notion about the current White House’s intention to reduce regulation reveals a lack of big-picture thinking. She intends to pack a $2 quadrillion economy into the 50 United States, but doesn’t anticipate the need for MORE regulation, not less – just to keep the human inhabitants from being utterly crushed by the fallout of that much economic activity. Naïve in so many ways.

So, here we have a column in National Review. It’s by a senior researcher at the Koch-funded Mercatus Institute (who formerly worked for the Koch-funded Cato Institute and American Enterprise Institute). It celebrates an interview produced by the Hoover Institution, with a Hoover senior fellow, conducted by a speechwriter from the Bush 1 and Reagan administrations. I’m just saying. These are growth propheteers working for the growth profiteers. (When you think about it, that is kind of like Disney’s Mouseketeers.) I could have predicted an economic growth and free-market love fest. And that is what we got. A very large grain of salt is in order.

For more realistic ideas about a healthy 21st century economy, check out our upcoming webinar, Joy of a Steady State Economy. It happens at 9pm EST on February 15. Details & Free Registration Here.

Tags: economic growth, economy, gdp growth, limits to growth, overshoot, sustainability

Trackback from your site.

Brian Sanderson

| #

GDP does not measure standard of living. But it might be more accurate to say that GDP measures how hard people are striving to increase their standard of living. That is to say, GDP measures the effort but not the outcome.

Thus, back in the 1950’s there was a plethora of new technologies that had obvious utility. There was also scope for rebuilding from the devastation of war. Obviously, people saw the possibility for improving their standard of living, so they made great efforts (high GDP) and those efforts were rewarded — reinforcing their motivation and effort.

Thus to say that the US economy presently has sluggish growth in GDP is to say that people see little hope for an improved standard of living and so they have, quite wisely, stopped trying so hard.

I’d be interested in what you and your readers think of this view of GDP?

Reply